This part of the page is still loading while I wait for the above traceroute to load.

Behind the Scenes

To reach this website, your computer sent some packets across the Internet. If we’re curious what that path was, we can run a tool to generate a traceroute — a rough list of every server your packets touched to reach their destination. To build this website (source code on GitHub), I wrote my own traceroute program called ktr (also open source) that can stream results in real time while concurrently looking up interesting information about each hop.

How does ktr work? Let’s start with a simplified explanation of Internet routing.

Starting with the source device, each computer that handles a packet has to choose the best device to forward it to — I will explain how these routing decisions are made in a bit. Assuming everything works correctly, the packet will eventually reach a router that knows how to send it directly to its destination.

My traceroute implementation uses a protocol called ICMP. ICMP was designed specifically for sending diagnostic information around the Internet, and, helpfully, almost every Internet-connected device speaks it. Interestingly, ICMP packets have a “TTL” (time to live) field. This isn’t actually a “time” as implied by a name — it’s a countdown! Every time a router forwards an ICMP packet along, it’s supposed to decrement the TTL number. When the TTL hits zero, the router should stop forwarding it along and instead send an error message to the packet’s source IP saying that the packet has reached its maximum number of hops.

We can take advantage of this TTL feature! To do a traceroute, we can send a bunch of ICMP packets with increasingly large TTLs. The first packet with a TTL of 1 will error on the first device it reaches, and so on, until we hopefully get an error back from every routing device that touched the packet. These error packets include diagnostic information like the IP address of the device that sent the error, allowing us to trace your packets’ rough path across the Internet.

Frontend Fun

This page will work perfectly fine with JavaScript disabled. From the browser’s perspective, this website just loaded slowly. From your perspective, a traceroute magically loaded in.

When you loaded this website, my program received a HTTP request coming from your IP address. It immediately started running a traceroute to your IP. Then, the server started responding to the HTTP request: it sent the beginning of this web page, and then it left the connection open. As ktr, my traceroute program, gave the server updates on your traceroute, it rendered the relevant HTML and sent it to your computer. When the traceroute finished, the server generated all the text and sent the rest of the website along the line before closing out the connection.

You may have noticed that the traceroute progressively loads in lines above the bottom line. Web pages can only load forward. Since I didn’t want to use any JavaScript, I did the hackiest thing possible: every time I update the traceroute display, I embed a CSS block that hides the previous iteration! Since browsers render CSS as the page is loading, this made it look like the traceroute was being edited over time.

Front to Back, Back to Front

My claim that this website’s traceroute was the path your packets took to reach my server was a bit of a white lie. To calculate that, I would’ve had to be able to run a traceroute to my server from your computer. Instead, I ran the traceroute from my server to your computer and just reversed it. That’s also why the traceroute at the top seemingly loads in reverse order.

Does running a “reverse traceroute” sacrifice accuracy? A little, actually.

As I said when describing Internet routing, each device a packet traverses makes a decision about where to send the packet next until it reaches its final destination. If you send a packet in the other direction, the devices might make different routing decisions… and if one device makes one different decision, the rest of the path will certainly be different.

This reverse traceroute is still helpful. The paths will be roughly the same, likely differing only in terms of which specific routers see your packet.

So, What Are All Those Networks?

This site began with talk about the “networks” you traversed to reach my server. What, concretely, are these networks?

Each network, also called an autonomous system (AS), is a collection of routers and servers that are privately connected to each other and generally owned by the same company. The owners of these autonomous systems decide the shape of the Internet by choosing which other autonomous systems to connect to. Internet traffic travels across autonomous systems that have “peering arrangements” with each other.

The Internet is often described as an open, almost anarchistic network connecting computers, some owned by people like you and me, and some owned by companies. In reality, the Internet is a network of corporation-owned networks, access and control to which is governed by financial transactions and dripping with bureaucracy.

If you want your own autonomous system, you can apply for an autonomous system number (ASN) with one of the five regional Internet registries (RIRs) that govern the Internet’s numbers. Be warned, they probably won’t listen to you if you aren’t backed by a company or you don’t have enough points of presence on the Internet. Just like we use IP addresses to identify—

Wait, what exactly do IP addresses identify? Uh… let’s say they represent devices with Internet access.

… Just like we use IP addresses to identify devices with Internet access, we use ASNs to identify the networks of the Internet. Those are the numbers like “AS63949” in the traceroute from the start.

Notes on WHOIS

One of the reasons I wrote a cool traceroute program myself is so I could pull information on which autonomous systems own the IPs along your traceroute. A couple of organizations try to keep track of which ASes contain which IP addresses. Many of them let you perform ASN lookups using the WHOIS protocol, so I wrote a small client to parse the responses from some servers I arbitrarily selected.

I then used this cool database called PeeringDB to figure out the companies behind the ASNs; PeeringDB has information on about 1/3rd of all autonomous systems. I used all of this information, alongside a couple hundred lines of if statements, to generate the text about network traversal for you.

WHOIS is actually an... interesting protocol to make a parser for. It turns out that the WHOIS protocol specification doesn't actually specify much. It specifies that you should make a TCP connection to the WHOIS server, send whatever you want to look up, and the server will send back some info and then terminate the connection. That’s all.

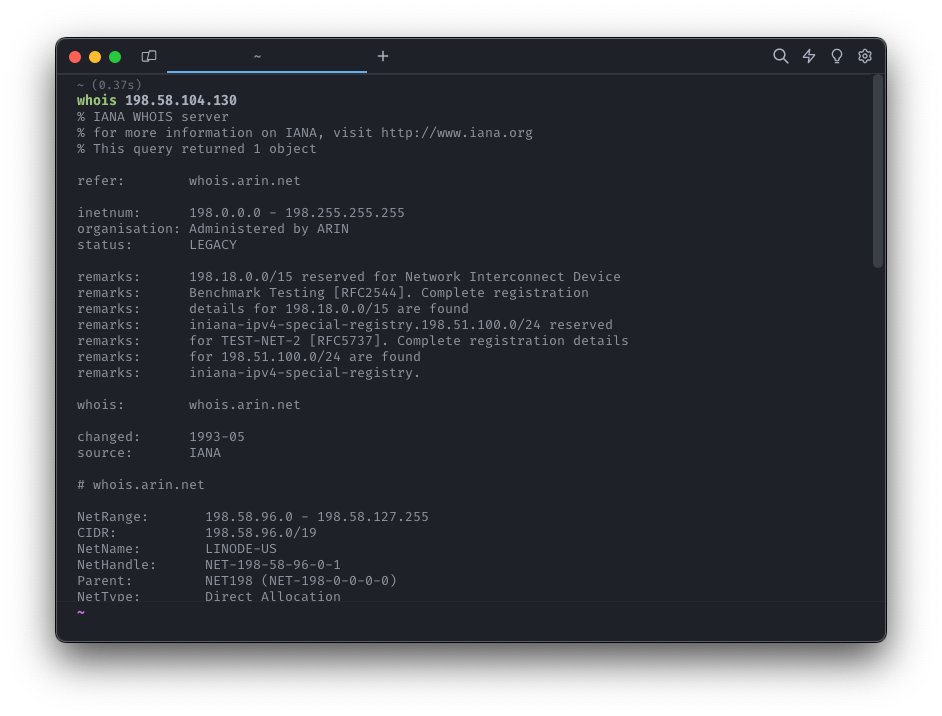

And yet, a lot of WHOIS servers will respond with structured-seeming information:

It turns out this structure is made up by the WHOIS server administrator and there just happen to be some shared conventions between servers. Even with the level of structure, the fields you want often show up with different names (origin? originas?) or even under multiple places at once.

My “parser” ended up as less of a parser and more as a lightweight simulator of how I, a human, might read through WHOIS results to find the ASN I need.

BGP

When you send a packet across the Internet, routers sitting at the borders where these networks connect decide which network to send your packet to next, until it reaches the network that contains the destination device.

These border routers talk to each other about which networks they’re able to connect to using a protocol called Border Gateway Protocol (BGP).

BGP is the protocol that gives the Internet its shape, and you can’t directly speak it yourself.

History Time

In 1969, the same year Neil Armstrong landed on the moon, a message was (partially) sent on a prototype of the ARPANET. Over the next 20 years, this “network of interconnected computers” thing got pretty popular and everyone wanted on the train. Various universities, government agencies, and a couple random companies started making networks of their computers left and right.

A couple of these organizations started connecting their networks together so they could share data more easily. The Internet as we know it didn’t exist yet, but these network interconnections were getting out of hand and there wasn’t a great standard for coordinating them. In 1989, engineers at Cisco and IBM published RFC 1105, describing the first ever version of BGP.

Over the next couple of years, interconnected-network people got really busy as “the Internet” rapidly became a thing. Just one year after the BGP v1 RFC, Cisco went public and brought a lot of money into the networking industry, the term “IANA” was first used to refer to the random guy and his college department that were keeping track of numbers on the Internet, ARPANET shut down for good, and BGP v2 was released.

In 1994, as the Internet-is-a-thing-now whirlwind was just beginning to calm, the final major version of BGP, v4, was specified in RFC 1654. It was revised twice (in 1995 and 2006) and got some patches, but BGP v4 is still the protocol we use for choosing routes across the interconnected networks that make up the modern Internet.

How Does This BGP Thing Work?

Routers at the borders between autonomous systems (“border gateways”) keep a list of every BGP route they know about, called a routing table. Each BGP route specifies the path of ASNs that could be followed to reach an autonomous system that controls a certain collection of IP addresses.

These routes across the Internet are formed by peering relationships between autonomous systems. When the border gateways of two autonomous systems peer, they are typically agreeing to:

Allow traffic to travel between the two routers, meaning BGP routes can go directly between the two ASNs.

Keep each other up to date about the BGP routes they know about.

Example time! Router A of AS0001 is physically connected with Router B of AS0002 and they want to peer with each other. They send BGP messages to each other to establish a BGP session. Router A now knows that it should go through Router B for any BGP route that starts with AS0002, and vice versa.

BGP peers share the routes they know about with each other in a process called route advertisement. In our above example, when Router A connects to Router B, it would tell Router B “hey, here are all the routes I know about, you can go through my ASN (and by extension, me) to reach all of them.” Router B adds all of those routes through Router A — so, starting with AS0001 — to its routing table. Whenever another one of Router A’s peers advertises a new route, Router A will advertise those forward to Router B.

AS0001 probably directly controls some IP addresses itself. Router A would advertise those to Router B as well. Router B would then, in turn, advertise those direct routes forward, telling its peers that AS0002 → AS0001 is a valid route to reach those IPs. Through this process of forwarding route advertisements to peers, BGP routes are propagated across the entire network of autonomous systems such that any border gateway hopefully knows one or multiple AS paths to reach any IP on the Internet.

To route a packet to a certain IP, a border gateway first searches its routing table for every route that would bring it to an AS that controls that IP. The router then picks the “best” route by various heuristics that include looking for the shortest path and weighing hardcoded preferences for or against certain autonomous systems. Finally, it routes the packet to the first AS in that path by sending it to that AS’s gateway router which it is peered with. That router, in turn, looks at its own routing table and makes its own decision about where to send the packet next.

Recap

When you loaded this website, it used my custom traceroute program to run a traceroute to your public IP (3.144.93.6), stream that over HTTP, and then render a textual explanation of the traceroute.

A traceroute depicts the path of routers traversed between two devices on the Internet. My particular implementation works by sending ICMP packets with increasing TTL fields.

These routers are in networks called autonomous systems. Routers on the edges of these ASes peer with each other using BGP. Border routers use BGP to share their routing tables with each other, and then use this knowledge to make routing decisions.

BGP peering sessions are created according to (often private) arrangements between the owners of autonomous systems. Since traffic can only pass between peered networks, these arrangements are the sole governor of reachability on the Internet.

Epilogue

I was frustrated with the state of understanding on the structure of the Internet and sought to write a comprehensive, interactive article covering its history and politics through the lens of protocols. However, I got caught up in a lot of complexity in life and, facing tight deadlines, didn't have the time to reach the lofty goals I had set for myself.

Thanks to the encouragement of my friends at Hack Club, I made the best out of what I had. “Better to ship a tiny raft than never ship that cruise yacht!” If nothing else, I got to make use of the sick ass traceroute program that powers the shiniest part of this site :)

I hope this serves as another fun, informative, and well-crafted thing on the web that can last, be shared around, and inspire people.

With love,

Lexi

Other Stuff

Some things to check out:

Proudly open source: